MASSACHUSETTS (2017)

*This project description was presented at the third convening of Sightlines, a festival and conference sponsored by the Screen & Sound Cultures research group within RMIT University’s School of Media and Communication, in December 2019. My talk was titled, The Reality That Never Was: An Undeveloped Practice of Virtual Reality, and it examined the development of creative virtual reality and immersive media practices in the university context, focusing on the problem of technical imperatives when it comes to critical learning in creative new media authoring. The case study I presented was my unfinished virtual reality short fiction, MASSACHUSETTS.

To highlight the ‘impotential’ of VR production I submit MASSACHUSETTS, an unfinished virtual reality short fiction produced as part of a trial graduate course in virtual reality production at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts in the spring of 2017. This course brought together about 15 students from various backgrounds – including film production, animation, architecture, game design, and one daunted PhD student in myself – to form small teams to complete two VR shorts, one prerendered and one rendered. Most folks elected to combine the two, producing a prerendered project to be completed as a rendered interactive experience. Our instructor was Associate Professor of Practice Eric Hanson – a VFX artist and co-founder of X-Rez Studio in LA, which specializes in photogrammetry, giga-photos, and stereoscopy, primarily for use in VR/AR/and XR.

The concept was to create a VR experience that utilized its unique affordances – to incorporate the 6 degrees of freedom promised by room-scale VR, to use the space of the experience to inform the narrative, and to force the user-viewer into a position where they must make a choice as to how they interact with what they see and hear. The title “MASSACHUSETTS” has little significance as it was a place-name that became a signifier of the project’s incomplete status. As a note: I fully own up to the corniness of the premise, and acknowledge that it was entirely informed by a bad break-up at the time. The slug line reads: “The ephemeral media of memory lingers in the house of a dead man.”

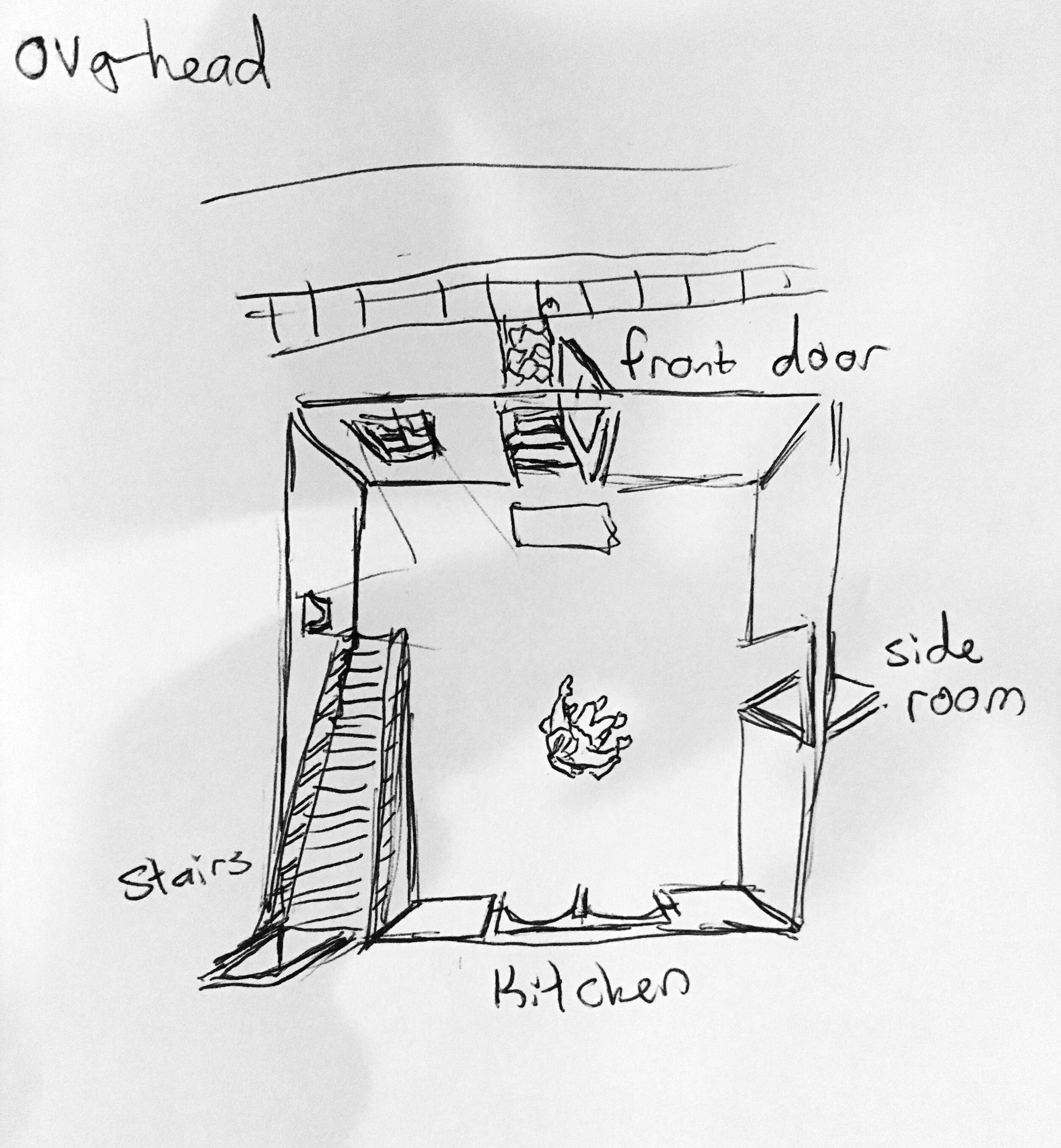

The experience opens on a foyer of an old house, which expands in three directions to a living area, a dining room, and a stairwell respectively. User-viewers are confined to the foyer – they can walk around the small area but cannot enter the living room, dining room, or climb the stairs. A body can be seen sprawled out on the floor and a prescription bottle lays next to it.

The nighttime scene quickly fades and the house brightens with sunlight; the body disappears. As the experience continues, audiences are presented with small dialogue scenes taking place in either of the three conjoined areas. These scenes often play simultaneously, so you have to choose which to pay attention to.

The story follows Victor, who we learn was the body at the beginning of the experience, his brother Henrik who has come to visit, and his significant other, Letha. We slowly pick up that Victor and Letha have split, at least in some regard, and she is in the process of moving out. We see her packing her things and fighting with Victor. Victor becomes increasingly distressed and more and more reliant on whatever pills he keeps popping from a prescription container. Henrik is there to intervene and tries to help his brother cope with the breakup.

As the experience progresses the timeline of events is muddled, scenes repeat themselves and vary in intensity and outcome. The house slowly empties and the foyer fills with objects we’ve seen the characters interact with, objects presumably containing the memory of their use – Victor’s guitar, Chinese food boxes that Victor and Letha share, the prescription bottle. These objects are photogrammetric models that the user-viewer can pick up and inspect. As Victor grapples with the trauma of his changing surroundings and his receding memory, retreating further and further inside himself, the user-viewer is invited to also literally grapple with the physical objects of memory. A genuine engagement and experiment in spatial storytelling, the experience is meant to investigate the media of memory and memory of media, how memories are assigned to spaces and objects and how the past invades the present in unexpected and sometimes unwelcomed ways. It’s also meant to test how VR addresses its audiences, how it implicates the audience and where it fails.

The aesthetic goal was to give the effect that lightfield technology promises, to combine photogrammetry and prerendered recording to create a three-dimensional space with live-capture stereoscopic video that you could also interact with

the Jaunt One VR camera

Our camera was the Jaunt One, gifted to USC as part of the fledgling Jaunt Lab at the School of Cinematic Arts, now defunct I believe. The Jaunt One has 24 individual HD cameras that support up to 8k resolution. The camera was connected to a laptop that would upload individual shots to Jaunt’s Media Maker, which would begin processing them as lat-long 360-degree video. Our camera operator David Nessl was the only one given access to Jaunt’s platform and the only member of our team insured to use the camera.

To minimize start-and-stop time, we would do multiple takes at a time without cutting, which proved difficult once it came time to edit.

Ultimately we would use 360-degree plates and photogrammetry to create a model of the set to bring into Unity. The video would be placed on “cards” and integrated into the set. Because user-viewers were confined to the foyer, they couldn’t approach the video and characters, and would have to view them from a short distance, which also would lend the videos a small degree of parallax despite their flatness.

We had a one-day, 12-hour shoot to accomplish a lot: shoot all the scenes and their variants, shoot the photogrammetry with the appropriate lighting (this aspect was the most time-bound), all the while changing the production design according to the script. We shot by area, so while I directed the stairwell scenes, Charlie could shoot the photogrammetry in the living room and our PD Lindsey could set up the kitchen…at least that was the idea.

We had three simultaneous sound recordings – the Jaunt camera mic, a boom mic, and an ambisonic recorder. Because ambisonic and 360-sound editors were nascent and unreliable at the time (we eventually used Facebook’s 360 audio editor, which was a nightmare according to our sound mixers…), having all three recordings covered our bases but also made the mix that much more cumbersome.